The renowned Singaporean artist Liu Kang (1911–2004) was a pioneering figure in the Nanyang art movement, which fused the artistic traditions of the School of Paris and Chinese ink painting with remarkable stylistic innovations. We learned this the hard way… As Liu Kang’s painting technique evolved significantly over his seven-decade career, understanding the technical details of his artistic process is crucial for conserving and interpreting his works.

Now, this might seem counterintuitive…

The Emergence of Liu Kang’s Nanyang Style

Liu Kang’s artistic journey began in Shanghai, where he graduated from the Xinhua Arts Academy in 1928. He then moved to Paris, immersing himself in the vibrant creative scene of Montparnasse from 1929 to 1932. During this highly productive period, Liu Kang studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and assimilated the essence of Western masters, developing a Post-Impressionist painting style.

In 1933, Liu Kang accepted a professorship at the Shanghai Art Academy, shifting his focus to teaching and painting. However, his artistic development was soon disrupted by the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, which prompted him to emigrate to Malaya (now Malaysia). After the war, Liu Kang permanently relocated to Singapore in 1945 and continued painting, primarily during trips across the region.

It was not until the 1950s that Liu Kang formulated his pivotal Nanyang painting concepts, which would define his artistic career for decades to come. Inspired by the Belgian artist Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Merpres and the French Post-Impressionist Paul Gauguin, Liu Kang embarked on a month-long painting journey to Indonesia in 1952 with fellow Singaporean artists Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Wen Hsi, and Chen Chong Swee. Their trip to the Indonesian island of Bali proved to be a turning point, as it sparked the establishment of the Nanyang artistic style.

The Nanyang style is characterized by paintings that express a regional identity among migrant Chinese artists in Singapore, stemming from an erosion of ties with mainland China, especially after the start of communist rule in 1949. The style reflects an eclectic amalgamation of the School of Paris and Chinese ink painting, representing Southeast Asian subject matter. However, a formal description of the Nanyang style remains elusive, as it did not evolve into a coherent art movement with an agreed manifesto.

According to Liu Kang, the essential components of the Nanyang style should include: “(1) the subject matter might want to be of Nanyang (the South Seas), generally confined to scenes of nature and social activities; (2) the technique and expression should be subjective, utilizing a simple, plain, and lyrical manner to depict the natural or human landscapes of Nanyang; and (3) the use of bright and cheery light and colours should be maximized and coordinated with fluid yet steady brushstrokes and lines.”

Investigating Liu Kang’s Painting Materials and Techniques

Although Liu Kang’s painting style and artistic concepts have been extensively studied, a comprehensive examination of his painting materials and techniques from the crucial 1950s period, when the Nanyang style emerged, has not been undertaken until now. This technical study aimed to characterize the painting supports, pigments, and methods used by the artist during this transformative phase of his career.

The research focused on a collection of ten paintings by Liu Kang from the National Gallery Singapore, spanning the years 1950 to 1958. This selection provided a unique opportunity to investigate the technical and stylistic evolution of the artist’s work, including paintings created shortly before and after the pivotal trip to Bali in 1952.

Painting Supports and Ground Layers

The investigation revealed that Liu Kang primarily used commercially prepared linen canvases, which he likely purchased in lengths and then cut to the desired size. Four distinct weave densities were identified, with the most dominant being a consistent thread count of 13 × 15 per cm.

Analysis of the ground layers showed that Liu Kang favored a double-layered oil-based preparation, with the bottom layer typically containing a high concentration of lead white mixed with lithopone, barium white, and zinc white. The top layer was often characterized by a greater presence of titanium white. Less frequently, the artist used single-layered grounds composed of zinc white or lead white with chalk, as well as a semi-absorbent ground containing an emulsion of oil and animal glue binders.

The discovery of empty nail holes on the tacking margins of the paintings suggests that Liu Kang did not always use the original auxiliary supports, which were likely of poor quality and made locally. This finding indicates that the artist may have reused canvases in the past, potentially impacting the provenance and dating of his works.

Pigment Analysis

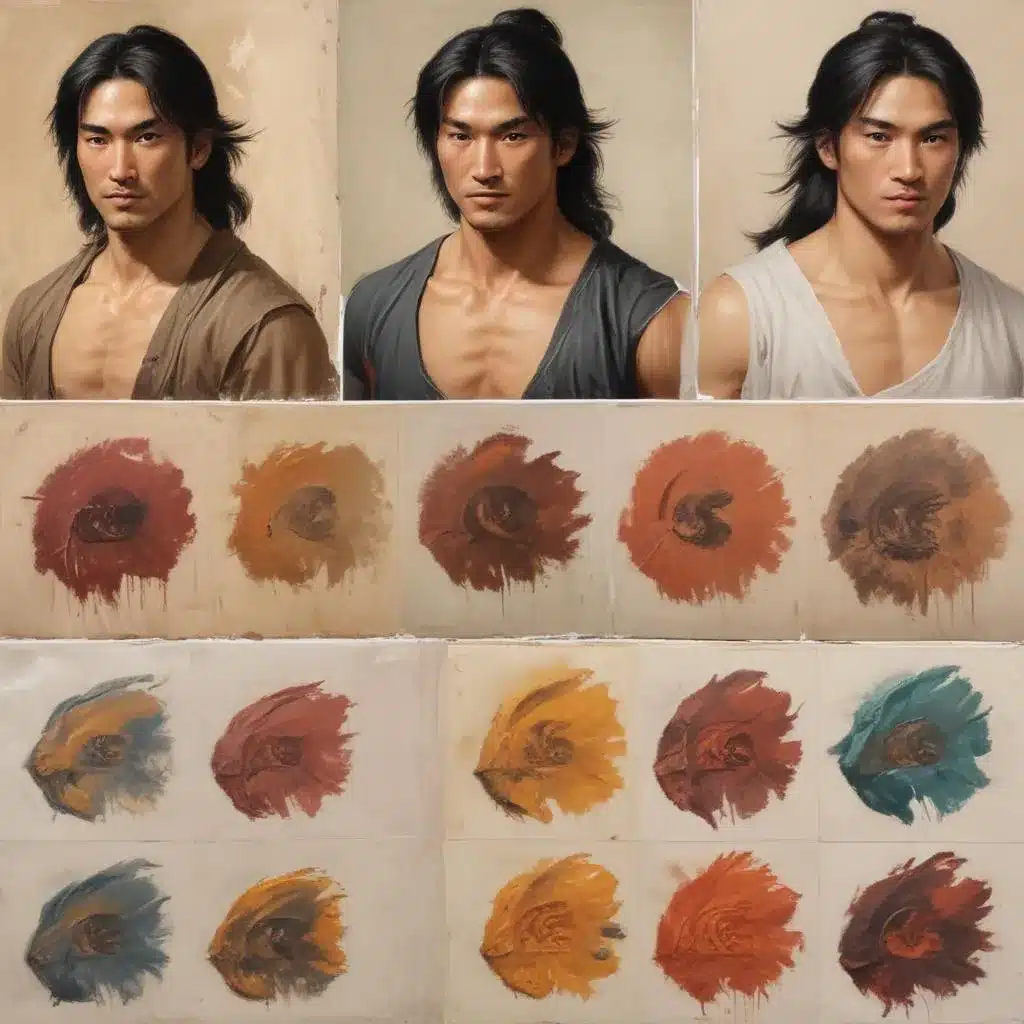

The comprehensive pigment analysis revealed that Liu Kang’s palette during the 1950s was diverse, incorporating both traditional and newly available synthetic pigments. Ultramarine and Prussian blue were frequently used in the blue passages, while viridian was the predominant green pigment, often mixed with cadmium yellow, zinc yellow, or both.

Interestingly, the study identified the sporadic use of some less common pigments, such as manganese blue, cerulean blue, cobalt blue, phthalocyanine blue, and phthalocyanine green. The presence of these pigments, which were not part of Liu Kang’s earlier painting practice, suggests that the artist was experimenting with new materials during the Nanyang period.

For the yellow and red hues, cadmium yellow and its variants, as well as organic red pigments like eosin-derived geranium lake, synthetic alizarin lake, and naphthol red AS-D, were extensively employed. The analyses also revealed the occasional use of chrome yellow, yellow iron oxide, cobalt yellow, and cadmium red.

The findings did not fully corroborate the 1955 account by the prominent Singaporean artist Ho Kok Hoe, who had stated that vermilion, viridian, and Prussian blue were Liu Kang’s “important” pigments during that period. While viridian was confirmed as a favorite, vermilion was not detected, and Prussian blue appeared more as an admixture rather than a primary blue pigment.

Painting Techniques and Processes

The study of Liu Kang’s painting process revealed a distinctive conceptual phase involving the consistent use of drawings and photographs. These preparatory studies allowed the artist to capture interesting subjects and motifs for future reference, minimizing the need for extensive underdrawing on the primed canvas.

The analyses identified four distinct painting approaches that suggest an evolution of Liu Kang’s methods of expression, culminating in the innovative style seen in Outdoor Painting (1954) and Painting Kampong (1954). These approaches include:

-

Flat and Broad Application: Liu Kang’s early works from 1950 to 1953, such as Village and Government Office in Johore Bahru, exhibit a broad and flat application of local colors with minimal suggestion of light effects and details.

-

Descriptive and Decorative: Paintings like Scene in Bali (1953) and Offerings (1953) display a more descriptive and decorative approach, possibly due to the artist’s fascination with the rich details and motifs of the Balinese subject matter.

-

Simplified and Geometric: In Outdoor Painting and Painting Kampong, Liu Kang abandoned the illusion of depth and focused on a conscious affirmation of the flatness of forms, achieved through solid colors and minimal paint texture. This style reveals inspiration from the dye-resist technique of batik textiles.

-

Reuse of Compositions: Some paintings, such as Boats (1956) and Char Siew Seller (1958), were executed over earlier rejected compositions, leading to a less precise delineation of forms and unintended impastos.

Throughout his painting practice, Liu Kang demonstrated a remarkable versatility in manipulating the medium, employing techniques like scraping into wet paint, building up impastos, enhancing shapes with outlines, and exposing the white ground of the canvas.

Implications for Art Conservation and Interpretation

The comprehensive technical analysis of Liu Kang’s paintings from the 1950s has revealed several crucial insights that impact the conservation and interpretation of his artworks:

-

Provenance and Dating: The evidence of reused canvases and modified compositions suggests that some aspects of Liu Kang’s painting practice may distort the provenance and dating of his works, requiring careful consideration during conservation and display decisions.

-

Artistic Evolution: The study of Liu Kang’s painting materials and techniques showcases the significant evolution of his artistic expression, from the broad and flat application of colors to the simplified, geometric, and batik-inspired style. Understanding this technical progression is essential for accurately interpreting the artist’s oeuvre.

-

Hidden Compositions: The use of X-ray radiography and infrared imaging revealed several hidden compositions underneath Liu Kang’s paintings, adding to our knowledge of the artist’s working methods and challenging the perception of his creative process.

-

Ethical and Aesthetic Considerations: The discovery of Liu Kang’s unconventional practices, such as painting over rejected compositions and working on the reverse sides of earlier artworks, raises important ethical and aesthetic questions about the conservation and display approach to his retouching work and double-sided paintings.

This research promotes the need for a comprehensive understanding of Liu Kang’s painting practice and the development of coherent guidelines to double-check that the proper presentation of his artworks and prevent misinterpretation of his technique and artistic outcomes. By shedding light on the technical aspects of his creative process, this study contributes to the growing body of knowledge about 20th-century artists’ materials and techniques, which are often characterized by complex mixtures of inorganic and organic compounds.

Tip: Experiment with different media to discover your unique style