The Spiritual Foundations of Human Functioning

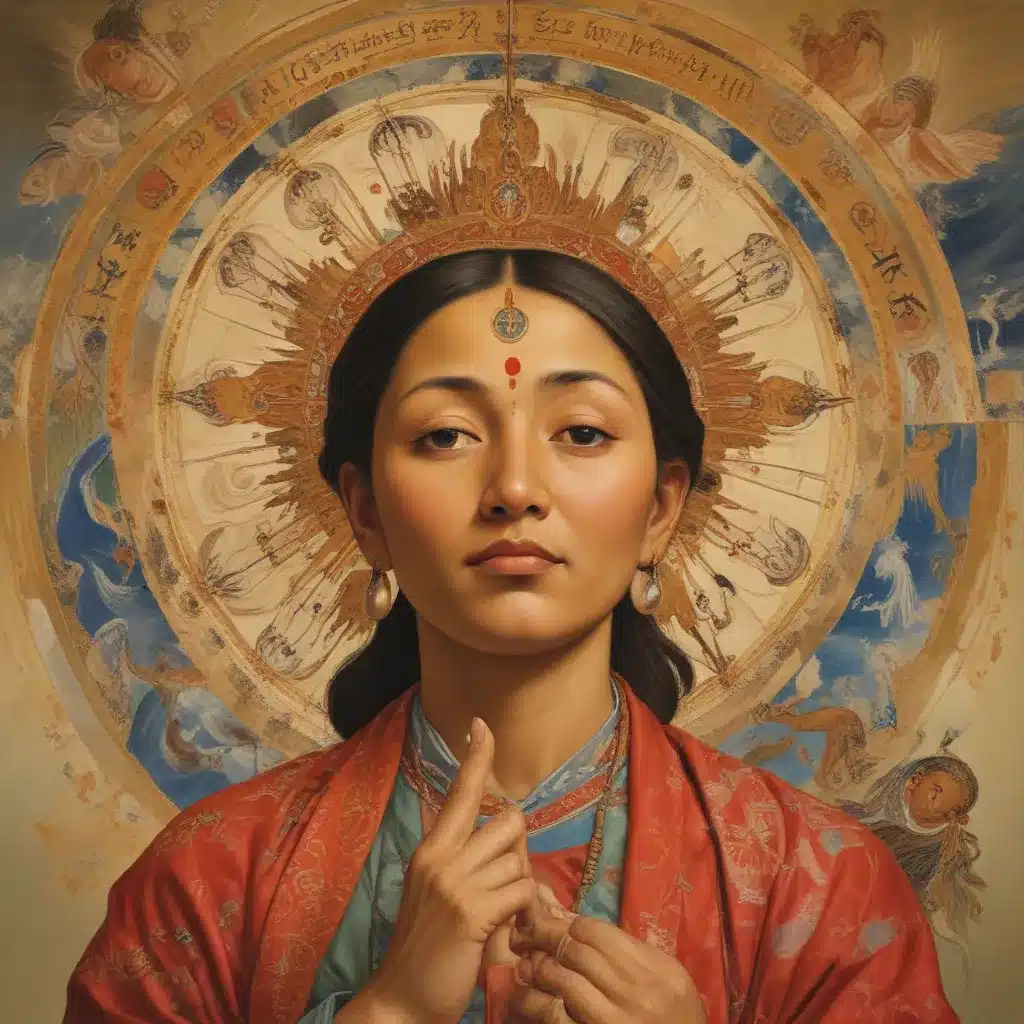

At the core of human existence lies an innate longing for transcendence – a yearning to connect with something greater than ourselves, to experience the sacred, and to cultivate a deeper sense of meaning and purpose. This profound spiritual dimension has long been a central focus in diverse fields, from philosophy and religion to the creative arts. Across cultures and throughout history, the human spirit has found myriad expressions, manifesting in sacred rituals, mystical experiences, and the creative impulse that infuses our greatest works of art.

In our modern, rationalistic world, the notion of spirituality can often feel elusive or difficult to define. Yet the desire to tap into this deeper well of human potential remains a driving force, shaping our personal growth, our relationships, and our very sense of what it means to live a fulfilling life. As the eminent psychologist and philosopher Jean Watson has observed, “Caring Science embraces the whole person, the unity of mindbodyspirit as one in relation with environment at all levels.” It is this holistic, integrative view that offers a profound lens through which to explore the intersection of spirituality and the human experience.

Drawing on the insights of Watson’s Caring Science theory, as well as the groundbreaking research on the multidimensional nature of spirituality, this article delves into the spiritual dimension that infuses the creative process and artistic expression across cultures and disciplines. From the visionary paintings of van Gogh to the transcendent poetry of Mary Oliver, we will examine how the human spirit finds voice through the arts, illuminating our deepest yearnings and connecting us to the sacred mysteries that lie at the heart of our existence.

Spirituality as a Multidimensional Construct

Defining the precise nature of spirituality has long been a challenge, as it encompasses a wide range of subjective experiences, beliefs, and practices that defy easy categorization. As the researchers from the NCBI study on the Expressions of Spirituality Inventory (ESI-R) note, “Despite such efforts, there exists a fair amount of divergence and disagreement regarding what does and does not constitute the content domain of spirituality.”

At the core of this ongoing debate are several key issues:

-

The Distinction between Spirituality and Religion: To what extent can spirituality be separated from religious belief systems and practices, or is it inherently tied to the sacred and transcendent?

-

The Complexity of Spirituality: How many dimensions or facets are required to fully capture the multifaceted nature of spiritual experience?

-

The Relationship to Well-Being: Are aspects of spirituality inextricably linked to psychological and emotional flourishing, or can spirituality be understood as a distinct realm of human functioning?

-

The Universal versus Cultural Specificity of Spirituality: Is spirituality a universal human phenomenon, or is it shaped by cultural and historical contexts in unique ways?

In exploring these questions, the research team behind the ESI-R has proposed a conceptual model that views spirituality as a natural aspect of human functioning, encompassing a range of interrelated dimensions:

Cognitive Orientation toward Spirituality: Beliefs about the existence, validity, and relevance of spirituality for one’s sense of identity and daily life.

Experiential/Phenomenological Dimension: Subjective experiences of the sacred, transcendent, and mystical, including changes in the perception of self and the world.

Existential Well-Being: A sense of meaning, purpose, and the capacity to navigate the existential challenges of life.

Paranormal Beliefs: Beliefs in the existence of phenomena that go beyond the material and physical realms.

Religiousness: Commitment to religious ideas, values, and practices for their own sake.

This multidimensional framework acknowledges the complex, nuanced nature of spiritual experience, while also recognizing the potential overlap and interconnectedness between these various facets. Importantly, it situates spirituality as a natural human phenomenon, distinct from but potentially influencing psychological well-being and other aspects of functioning.

Spirituality and the Creative Process

As we consider the spiritual dimensions of human experience, it becomes clear that the creative arts have long served as a primary conduit for the expression and exploration of the sacred. Whether through the visionary paintings of van Gogh, the transcendent poetry of Mary Oliver, or the soulful music of Debussy, artists throughout history have drawn inspiration from the wellspring of the human spirit, translating their deepest yearnings and insights into works that captivate and transform us.

The connections between spirituality and artistic expression are manifold. As the Caring Science theory proposed by Jean Watson illuminates, the creative process often involves a “transpersonal caring consciousness and intentionality” that transcends the individual ego, reaching toward a deeper, more universal realm of being. In this way, the artist becomes a conduit for something greater than themselves, channeling the sacred energies of the cosmos into tangible forms.

This spiritual dimension of creativity is evident in the words of the renowned painter Vincent van Gogh, who wrote: “I put my heart and my soul into my work, and have lost my mind in the process.” Van Gogh’s oeuvre, with its vibrant colors, expressive brushstrokes, and otherworldly visions, bears witness to the artist’s mystical connection to the natural world and the hidden rhythms of the universe. In works like “Starry Night” and “Sunflowers,” Van Gogh’s canvases become a portal to realms of the spirit, inviting the viewer to look beyond the material surface and apprehend the sacred energies that animate all of creation.

Similarly, the poetry of Mary Oliver speaks to the capacity of the arts to cultivate a profound sense of wonder, reverence, and ecological awareness. In her acclaimed poem “Wild Geese,” Oliver entreats the reader to “tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine” – a invitation to engage in a shared journey of spiritual discovery and emotional honesty. Oliver’s work is imbued with a deep respect for the natural world, recognizing it as a wellspring of wisdom and inspiration that can nourish the human soul.

And in the realm of music, the impressionist composer Claude Debussy found in the natural world a source of boundless creative potential. His symphonic sketch “La Mer” (“The Sea”) captures the shifting moods and rhythms of the oceanic expanse, drawing the listener into a sensory and emotional experience that transcends the merely material. Debussy’s music, with its shimmering harmonies and evocative tone colors, invites us to attune our senses to the sublime mysteries of the natural realm, awakening a sense of reverence and connection to the sacred.

Through these diverse artistic expressions, we glimpse the profound ways in which the human spirit seeks to make meaning, to connect with the ineffable, and to apprehend the deeper patterns and energies that imbue our world. The creative arts, in this light, become a vehicle for spiritual exploration and transformation – a means of illuminating the hidden dimensions of our existence and our place within the grand tapestry of the cosmos.

Spirituality, Nature, and the Indigenous Worldview

As we delve deeper into the spiritual wellspring that nourishes artistic creation, it becomes increasingly clear that the natural world occupies a central role. Across cultures and throughout history, human beings have turned to nature as a source of inspiration, solace, and sacred connection, recognizing in the rhythms and energies of the living earth a vital reflection of their own spiritual yearnings.

The research reviewed in this article points to the growing scientific evidence linking encounters with nature to heightened states of well-being, both in terms of hedonic (positive emotions, life satisfaction) and eudaimonic (meaning, vitality, transcendence) dimensions. Theories such as Attention Restoration Theory and Eco-Existential Positive Psychology suggest that the natural world provides us with opportunities to escape the demands of daily life, to restore our cognitive capacities, and to cultivate a deeper sense of identity, connection, and meaning.

Yet what is often missing from these scientific inquiries is an explicit consideration of the spiritual dimension that so often accompanies our experiences of the natural world. As the Jungian scholar David Tacey observes, Western culture has long been plagued by a “devaluing of ancient cultures” and a failure to recognize the “animism” – the sense of nature as a field inhabited by spirits and sacred energies – that has sustained indigenous worldviews for millennia.

The wisdom of indigenous peoples, such as the Canadian “Two-Eyed Seeing” approach, offers profound insights into the intimate links between spirituality, well-being, and our relationship to the natural world. These perspectives emphasize the importance of a “wholistic way of knowing, being, doing, and seeing” that integrates the mental, spiritual, physical, and emotional dimensions of human experience. Crucially, they recognize the “spirit in everything” and the essential role of our interaction with nature in achieving a state of balance, integrity, and responsibility toward the greater good.

In contrast to the Western tendency to view nature as an external, mechanical system to be conquered and exploited, these ancient worldviews invite us to recognize our fundamental interconnectedness with the living earth. As the renowned poet and environmental activist Wendell Berry reminds us, “There are no unsacred places; there are only sacred places and desecrated places.”

By embracing the spiritual significance of our encounters with nature, we may find that the creative arts can serve as a vital conduit for cultivating this sacred connection. The poetry of Mary Oliver, the paintings of van Gogh, and the music of Debussy all bear witness to the power of the natural world to stir the human soul, to awaken our senses to the hidden rhythms of the cosmos, and to inspire us to live in greater harmony with the living systems that sustain us.

Conclusion: Integrating Spirituality, Creativity, and Nature

In an age marked by growing disconnection, escalating environmental crises, and a deep hunger for meaning, the integration of spirituality, creativity, and our relationship to the natural world has never been more vital. As the research and insights explored in this article have illuminated, the human spirit seeks expression through myriad avenues – from the visionary canvases of the artists to the transcendent poetry that celebrates the sacred energies of the living earth.

By embracing a holistic, multidimensional understanding of spirituality, we can begin to uncover the profound ways in which this dimension of human experience shapes our creative impulses, our sense of purpose and well-being, and our fundamental connection to the natural world. The Caring Science theory of Jean Watson, the multifaceted model of spirituality proposed by the ESI-R researchers, and the wisdom of indigenous worldviews all offer valuable frameworks for navigating this rich and complex terrain.

Ultimately, the spiritual dimension of the human experience is not something to be studied in isolation, but rather as an integral part of our wholeness as individuals and as a species. It is through the creative arts, our encounters with nature, and our willingness to honor the sacred in all things that we may discover new pathways to personal and collective flourishing – pathways that celebrate the unity of mind, body, and spirit, and inspire us to live with greater reverence, compassion, and responsibility toward the web of life that sustains us all.